Read UCLA TFT’s Q&A with screenwriter, orientation speaker and honoree Billy Ray

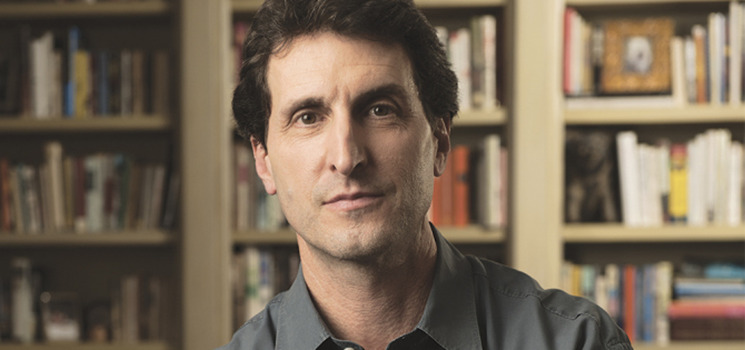

Academy Award-nominated screenwriter Billy Ray (BA ‘85) began his college experience at Northwestern University with an eye toward a career in journalism. But it didn’t take long for him to realize that what he really wanted to do was write movies. That decision led the San Fernando Valley native back to Los Angeles where he enrolled at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television and put him on a course that would lead to a rewarding and impressive career as a screenwriter, director and producer. His credits include The Hunger Games, based on Suzanne Collins’ best-selling novel; the fact-based dramas Shattered Glass, Richard Jewell and, most recently, The Comey Rule, a four-part Showtime event that took a look at the relationship between former FBI director James Comey and Donald Trump, whose strikingly different ethics and loyalties put them on a collision course. “I’ve made a lot of movies about my country,” Ray says. “That one was made for my country.”

Ray, who is this year’s Outstanding Alumni Award honoree, will be in conversation with screenwriting professor George Huang during UCLA TFT’s new student Orientation on Tuesday, Sept. 20. In anticipation of the event, he recently sat down with TFT’s Noela Hueso for a chat.

How did you break into the industry?

The first thing I ever sold was an episode of The Jetsons, the summer after my sophomore year at UCLA. I was 19.

Wow! You were 19?

Yeah, and those two summers, my sophomore into junior and junior into senior years, I interned for two TV movie producers who were in the Valley. Then, as I was about to graduate, I wrote to them and I said, “I need a job,” so, they made me their gopher. I wrote at night. Then I started to grow within the company and got a raise, but now I had to read for them every night. Pretty soon the only time I could write was on Sunday nights.

Did anything come of those writing sessions?

I wrote a script and didn’t sell it, then wrote five more drafts of it and sold it for such a low number that I couldn’t even quit my job, but it was enough to say I was professional writer. On January 8, 1988, I walked into 20th Century Fox with a pitch and sold that. Then I had enough money to quit my job for a year and try to make as a writer. I went like this [moves hand up and down] for a long time but always enough to stay in the game. Then I directed for the first time, a little movie called Shattered Glass, and in 2002, my career started doing this [moves hand in an upward direction]. Not without disappointments, not without the heartbreaks that made me want to roll on the floor and cry, but basically like that.

How did you walk into 20th Century Fox? Did you have an agent?

I had an agent by then because I had sold that first script and my sister worked for producer Gale Ann Hurd, so I pitched Gale the idea. I got every break a human being could get. I’ve been very, very blessed.

Did you always want to be a screenwriter?

Well, when I was 13, I wanted to be the first Jewish president. Then I ran for president with my junior high and I won, and I saw the seamy underbelly of politics up close and realized I just couldn’t stomach it. So, I went for show business instead.

And you’ve been a keen observer of politics ever since.

Well, I tend to write a lot about integrity. Maybe it’s because I’m not sure I have enough of it, but I tend to write stories that are about moral ambiguity that gives way to perfect moral clarity — and then what you do about it. I’m interested in stories that reflect America back to itself.

What are current events saying about us as a country right now, then?

That we’re in a struggle to find our soul. I think we will, but that we’re we are trying to lean towards community over chaos. We’re trying to scramble back to our roots, which have to do with liberty and democracy as opposed to authoritarianism.

When you’re writing, from where do you draw inspiration? I know you’ve done a number of adaptations.

I’m happily at a place in my career where I get to pick what’s the thing I want to invest my sweat equity in, and that’s a great thing to be able to do. But everything that I get comes out of observing human behavior. So, it has to do with getting on a plane and going to the place I’m writing about and talking to people. That’s how Comey got written. That’s how Shattered Glass got written. That’s how everything that I’ve worked on gets written: I go talk to them and approach it like a journalist. I bring a pad and take notes and get it right and double source if I can. I find authentic human behavior much more interesting than anything I can come up with and create, which is why I tend to do more of it.

Yet you’ve also written sci-fi, which is completely different.

Yes, but in the case of The Hunger Games, before I started writing that one, I decided that was a true story, too. Something in my head said, “This is true; there’s a government, it’s doing it to these children,” and I was so appalled that I wrote that from a very angry, righteous place, and I think that made a difference.

In general, would you say that you write to entertain or to educate?

You have to entertain. Screenwriting is an intellectual exercise designed to elicit an emotional response. Golden rule of writing. If I write a script and I give it to a friend and that friend says to me, “This is the smartest script I’ve ever read,” I have failed 100% because I’m right here [points to his head] and not in their guts. When you’ve written a script that works, that friend calls me and says, “Oh my God, I love this. I can’t believe you killed that guy. I was so sad; I was so scared.”

I recently heard the NPR journalist Scott Simon ask one of his interviewees, “Is imagination more important than craft?” What are your thoughts on that?

That’s a tough one because you can’t survive without both. But what I will say is that I can teach craft to any aspiring writer, but I can’t make them a writer. I can’t teach them imagination or give them an ear for dialogue. I can’t inspire them to create characters. That’s something that is God-given and then developed.

What advice do you have for aspiring screenwriters?

Never let anybody out-work you. Never let anybody out-hustle you. If you were a mechanic, you wouldn’t go to Starbucks for two hours and wait for your muse to land on your shoulder and say, “Fix the carburetor.” You would just go fix the carburetor. Pretend you’re a mechanic. Ninety-five percent of what we do as screenwriters is problem solve. It’s “that works” or “that doesn’t” and “how am I going to make it work?” We’re just trying to make the engine run.

How do you know when something works and when it doesn’t?

When it doesn’t bore me. Same thing when you’re directing and watching a scene: If your attention wanders, the scene isn’t working. If it makes you cringe, it’s going to make other people cringe, too. So, you do it until it feels real and true and authentic and human and imperfect and idiosyncratic in the way that life does. Then you give it to people who you trust and make sure that they’re not bored and then you give it to the people who can actually affect your career.

What is your next project?

I’ve written a miniseries about January 6th.

How’s that coming along?

It was written originally for Showtime, and now I’m trying to find another home for it. I don’t tend to give up on things even after networks or studios do. These things are your children, and you have to take care of them.