Lap Chi Chu, Helping Make A Classic Musical Relevant For A New Audience Is All About The Right Lighting

By Noela Hueso

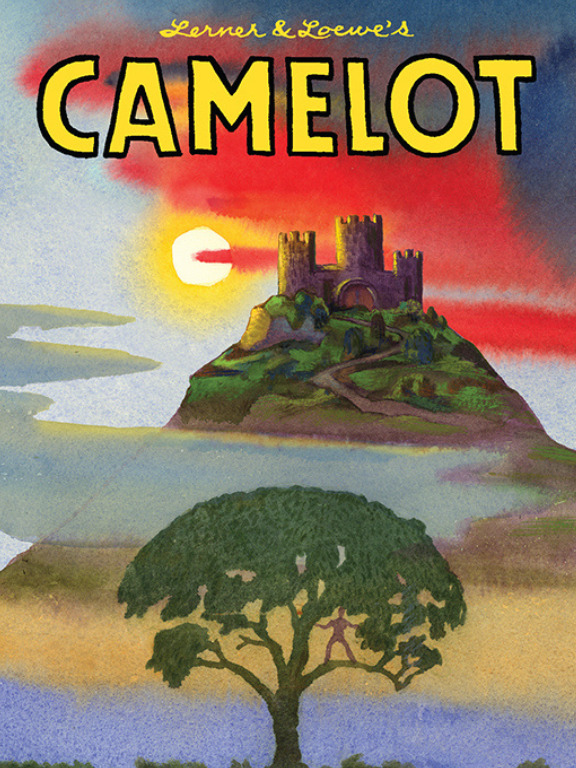

Camelot. For many, the word evokes the glamour of the Kennedy administration as much as it does Lerner and Loewe’s classic 1960 musical centering on the fateful relationships between King Arthur, Guinevere and Lancelot. For lighting designer and TFT Professor Lap Chi Chu, it represents an opportunity to add a Broadway credit to his already impressive resume as he prepares to stage the latest revival of the show alongside his friend Bartlett Sher, the Tony Award-winning resident director of New York City’s Lincoln Center Theater. (There have been three revivals to date, as well as numerous tours, two West End productions and a 1967 film adaptation). With a new book by Academy Award-winning screenwriter Aaron Sorkin, previews begin March 9; opening night is set for April 13. Chu recently took a break from his work to talk about Camelot, his lighting vision for the production and how putting on a show really is an evolving process.

Aaron Sorkin is doing the book, so I’m guessing this production is going to be a little different from Alan Jay Lerner’s original text.

Yes, it’s certainly a revisit. If you look at the old movie version, it was a different time, and a different point of view. This version will be a bit about idealism and the decline of perfection. We’re taking a look through the eyes of Aaron Sorkin and Bartlett Sher and what it means to do it today.

What are the emotions that are evoked in Camelot? It’s a love story, but what else is there?

Conflict. Debate. Arthur is trying to make Camelot an ideal space but then that breeds somebody like Lancelot who is a zealot, who is idealism to an extreme — and I’m sure we could think of parallels in today’s world. That’s the balancing act and the debate on top of the love story.

How does that play out in lighting?

We threw out some early design ideas that were very illustrative but we’re going to be a little more stylized, a little more modern. We’re going to have video projections. To be over-simplistic, because the story is about idealism, it needs to be pretty, and it will give us something to lose when idealism is gone at the end of the story. It sounds inadequate to just say, “Oh it’s going to look pretty,” but it is integral to what Camelot needs to represent.

What are the “pretty” colors?

I tell our students: You don’t pick one color, you pick palettes, so that’s what we’re going to do. I don’t believe in color coding; I can make night any color; it doesn’t have to be blue — there could be an amber evening. I always say, let’s see where we came from, the scene before, and where we need to go. There’s always a pretty version of every color.

What do colors look like when things aren’t pretty anymore?

They might be monochromatic, bare and stark, and maybe as much about angle; then it’s just a single sweep of something; less lush — this is the volume of color and light. We’ll have that plan but I’m not going to be married to it.

It sounds like the look of the show evolves as you go through the process of putting it together.

Yes. You find out a lot when you actually put it on its feet in the theater — what the visual storytelling is versus the words. We’re going to learn about that once the set is all loaded in and painted. We focus all the lights, we go through a couple of weeks of tech. In the process, we learn what the visuals tell Aaron and Bart and what changes they may want to make to help tell the story more effectively. Bart is very good about reacting to what he’s seeing; he’s a good editor; he doesn’t insist that it needs to fit his original conception of it.

Tell me more about the set.

It has a big ramp rake, and the stage is about 70 feet deep. It’s a really long space and they’re using as much as they can as a playing area, so it gives me a good opportunity to have that floor as a visual palette. We can put somebody far away and really have that distance to be able to create a landscape that way. Scale-wise, this will be the largest set I’ve worked in, so it’s going to be exciting to really see what that looks like.

Are you playing with particular shapes?

When the audience walks into this ginormous space, they’ll see it covered in large pieces of white fabric. It’s very neutral. Then just as the show is beginning, those giant pieces will be ripped away and uncover the set. We’re trying to give them no shape, to start.

If the sets are suggestive, how will the audience know where they are at any point in the story?

There’s still the need to recognize that the actors are on the hillside; they’re in Arthur’s bed chambers; they’re in the Round Table with the Knights; so, the stage needs to transform to all those places and times without changing the entire set. We’re suggestive with pieces, but lighting helps articulate that and transform the space. It typically does that a lot faster than pushing on a bed in the scenery.

How are you handling scene changes?

We’re going to keep the storytelling going; we don’t want to lose momentum. Bart is very good at keeping the audience on the hook and lighting helps do that; when one wall is going away and the bed’s coming on, we’ll keep the storytelling going somehow in between these moments of beauty that we’re putting in.

Has the larger stage presented any challenges to you so far?

It actually hasn’t been that much of a problem. If anything has been difficult, and it is a sign of the times, it’s supply chain issues. We put the order in, and we felt lucky that we got as much gear as we did. We had some limited availability. Given the scale of the space, we needed much bigger lights than usual. We have about 80 moving lights in this one, and we’ve got 250 feet of strip lights.

Is that enough? Did you have to make some concessions?

We ultimately got enough but some gear had to come from across the country.

Were you a fan of Camelot before coming on to this version of the show?

I didn’t know it very well, though I was always aware of it; the songs have been iconic since the original Broadway production in the ’60s. It wasn’t until I was older that I put two and two together and realized, “Oh, that’s the story, that’s what Camelot means.”