For Voiceover Narrator Scott Brick, The Career of Silent Film Star Asta Nielsen Spoke Volumes

By Scott Brick

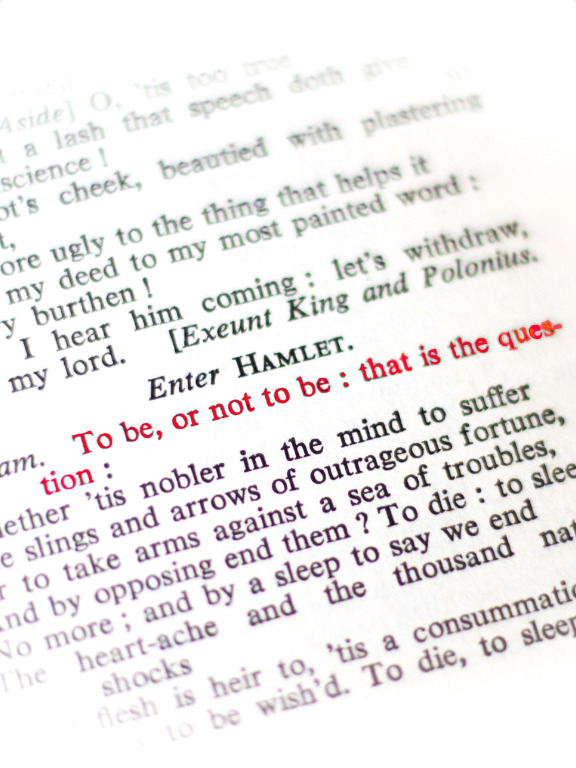

When I was a UCLA Theater student in the late 1980s, I attended a thought-provoking play written by my friend and fellow student Dana Stevens, a UCLA grad who has gone on to have a stellar career as a writer and filmmaker in Hollywood. Its name has long since faded from my mind, but I will always remember it as the first story that truly challenged me to think about privilege, in this case as it applies to gender. In it, Dana’s lead character bemoans the fact she may never play Hamlet simply because she was born a woman. I was captivated by the story partly because at that very moment I was playing Hamlet’s best friend Horatio in the Freud Playhouse production directed by the late Carl Mueller. Dana’s play made me appreciate every moment of that show, because I suddenly realized that there were probably many female actors out there who would have gladly switched places with me so they could play such a role, if given the chance.

But as we’ve learned in the decades since, gender is not as finite as I believed it to be and should never be a barrier. And how could I have known how wrong I was? How could I have known that, before Laurence Olivier created his classic 1948 movie, a woman had been the world’s best-known Hamlet on film? She was Asta Nielsen, and she was a force of nature.

I’ve always been fascinated with the silent film era. It may seem odd that a performer who makes his living narrating audiobooks and who’s had the privilege of teaching UCLA TFT’s third-year acting students the art of narration for six years now — that someone who quite literally talks for a living — would find himself fascinated by a time when performers couldn’t speak, but fascinated I was and remain. Decades after leaving school I asked my friends at Eddie Brandt’s Saturday Matinee video store in North Hollywood to steer me toward silent adaptations of Shakespeare’s work.

Behind the counter, my buddy Tony’s eyes went wide as he asked, “Ever seen the female Hamlet? German silent film, 1921.”

What? A woman played Hamlet on film…? My mind shot back to Dana’s play, and I eagerly took the DVD home and sat mesmerized in front of my TV.

Women playing Hamlet was nothing new, of course, but it was primarily done on stage. Indeed, one famous tour had the great Sarah Bernhardt playing the role, a single scene of which had been filmed in 1900 but was only two minutes long. Asta Nielsen’s production two decades later, however, was a marvel.

Born Asta Sofie Amalie Nielsen (September 11, 1881-May 24, 1972), she was the greatest Danish actor of the 1910s and is credited with being the very first international film star, challenged only by the French silent film comic Max Linder, remarkably even before Charlie Chaplin created his own worldwide sensation. Nielsen performed in 74 films, 70 of which were made in Germany, where she was known simply as Die Asta, or “The Asta,” a name I absolutely adore.

Known for her smoldering sensuality onscreen, Nielsen helped transform silent film acting from its more overtly theatrical style to one that is more subtly naturalistic. She was also a filmmaking pioneer: Not only was she the highest-paid movie star in the world in 1911 at $80,000 a year, but later that same decade Nielsen would storm into that male-dominated enclave of film production itself.

Her own company, Asta Films, produced her portrayal of the world’s most iconic character in 1921’s Hamlet: The Drama of Vengeance. Inspired by Edward P. Vining’s 1881 book, The Mystery of Hamlet: An Attempt to Solve an Old Problem, which was referenced in the movie, the film’s opening title card stated the updated dilemma immediately: Hamlet was actually a woman!

A work of literary research, Vining’s book posited that because Hamlet was weak and vacillating, who “does those things which he ought not to do and leaves undone those things he ought to have done,” the person we assumed was a he must therefore have been a she, right? Weakness isn’t a male trait, it’s a female one…isn’t it? Given what we’ve learned about gender fluidity in the century and a half since Vining’s book, however, we know now that the book’s central thesis was one prolonged eye-roll — “[Shakespeare] wrote ‘a new man,’ and I think today we are still questioning what it is to be that man, to be any man, in fact,” says actress Cush Jumbo, who played Hamlet at London’s Young Vic in 2020 — but the book’s very existence allowed Nielsen to play artfully with the text during a less enlightened decade, all with the luster of literary theory to lend it credibility, making it possible for Germany’s greatest living actress to make a role traditionally played by a man available to a woman.

The film opens with Queen Gertrude giving birth. Believing her husband has died in a foreign war and knowing that the crown will only pass to males, she loudly declares to her subjects that her newborn daughter is in fact a son, the dead king’s heir. Upon King Hamlet’s safe return, however, there is no way to undo Gertrude’s earlier proclamation, so they are forced to raise their daughter as “Prince” Hamlet, which creates quite the unique love triangle! Hamlet falls in love with her best friend Horatio, who, not knowing that she is a he, falls for the fair lady Ophelia, who herself pines away for the dour, mysterious “Prince” Hamlet. When Horatio, his head resting upon Hamlet’s lap, admits his feelings for Ophelia, Hamlet reacts with fury and sets out to thwart Horatio’s plans by wooing Ophelia herself, only to spurn and ridicule her after her heart has been won, which is a brilliant and eminently believable take on how things go so wrong between Hamlet and Ophelia in Shakespeare’s original.

Thankfully, the film still exists and is readily available both on DVD and online. Moody and artfully lit, the movie stands not only as a pioneering foray into gender fluidity nearly a century before the subject became so vital but is also a shining example of powerful women in cinema’s earliest years. On both fronts, it is a story that should inspire people everywhere. Sadly, Nielsen’s overt sensuality and erotic style came up against America’s earliest censors, which resulted in her films finding relatively few takers among domestic distributors of the 1920s. Still, The New York Timespraised Nielsen’s performance in Hamlet: The Drama of Vengeance and called it an extraordinary work, saying, “It holds a secure place in the class with the best,” and later named it one of the 10 best films of the year.

In 1925, Nielsen starred in Die Freudlose Gasse (aka The Joyless Street and Street of Sorrow) for Austrian director

G.W. Pabst and a completely unknown co-star named Greta Garbo, mere months before the latter left Germany for Hollywood, a contract at MGM, and a lifelong struggle with fame. Pabst would later say of Garbo and Nielsen, “One has long spoken of Greta Garbo as ‘The Divine,’ but for me, Asta Nielsen has always been and will always remain ‘The Human Being’ par excellence.” Garbo herself once observed of Nielsen, “In terms of expression and versatility, I am nothing compared to her.”

Coming from The Great Garbo, I can think of no greater epitaph.

Nielsen retired from film in the 1930s and went on to a rewarding career in literature, art and photography. She gave birth to a daughter she adored, then, at the age of 88, married the love of her life and spent their final two years traveling the world. Although the public never appreciated her quite enough before her passing at the age of 90 in 1972, film theorist Bela Balazs wrote, “Shakespeare is reputed to have used 15,000 words. When our first dictionary of the language of gesture has been compiled with the help of cinematography, only then can the expressive treasures of Asta Nielsen be appreciated.”